Trade Carbon Credits Actually Work

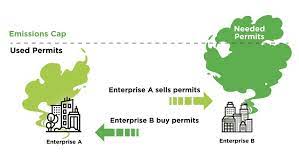

For those unfamiliar with carbon credits, they’re financial instruments that are used to offset a company’s carbon footprint. Companies that produce a lot of carbon emissions buy them from a third party so they can meet their environmental goals and stay within the limits of the cap-and-trade system in place in Europe. The market for these credits is growing rapidly. As more and more companies make net zero pledges, they’re looking for ways to fund the projects they need to do so. And that’s where the voluntary carbon markets come in.

The problem with these markets is that they’re unregulated and there’s no clear way to verify whether the credits are really worth what people are paying for them. For example, the accounting and verification methodologies are different for every trade carbon credits project, and some of them have other benefits like biodiversity protection or community economic development, which buyers don’t always pay attention to. Moreover, the process of matching buyers and sellers requires long lead times, which can increase issuance costs and reduce liquidity in the market.

That is why several organizations have started to try to fix this mess. One of them, Verra, was launched in 2007 by business and environmental leaders to set a standard for high-quality carbon credits that can be traded in voluntary markets. The group has registered 1,750 projects and verified almost 796 million carbon units since then. Its goal is to “make sure that the buyer has confidence that the carbon they’re purchasing actually represents real emission reductions and is credible,” its CEO tells NBC News.

Do Trade Carbon Credits Actually Work?

There is also a global effort to develop a regulated carbon market, and the UN secretary general has established a task force that’s aiming to get everyone on board by 2050. But that’s a huge undertaking, and it would require a global agreement on rules for a new market for carbon credits, along with the necessary infrastructure to support it. Developing such a system could take a decade or more.

The problem is that the carbon offsets that companies are buying often don’t do what they say on the tin — they don’t actually cancel out or reduce the greenhouse gases that pollute the atmosphere. Instead, they usually end up funding action that wouldn’t happen otherwise, such as tree planting, renewable energy, or efficiency improvements in poor communities. That’s not to say that these are bad things; in fact, they’re important. But they’re not the kind of emissions reductions we need to avoid climate disaster.

Until there’s a more stable system for buying and selling carbon credits, the voluntary market will likely continue to grow. But it needs better safeguards in place if it wants to keep up with the extraordinary demand for high quality, credible carbon credits from businesses that want to make their net zero pledges. That’s why we need to put more of a focus on regulating these markets in the same responsible fashion as other financial markets.